LACHRIMAE: Hoang Duong Cam

Past exhibition

Overview

The exhibition title, LACHRIMAE, takes inspiration from the titular song by the English composer John Dowland (1563 – 1626), who was widely known for his masterful and complex musical explorations of melancholy. Also known as The Seven Tears, the piece comprises seven different pavanes — a type of Elizabethan processional dance, which was used to carry the couples to the front of the court [1]. In each pavane, John Dowland portrays different emotional stages of tears, which range from despair, grief, and fear to sanctity, compassion, and hope [2]. Of the famed composer’s archetypical plunge into melancholy and its manifold nature, Lachrimae reflects the condition of his time: an in-between period as Europe transitioned from the end of the Renaissance and ushered in the beginning of the Baroque period. The period was governed by melancholy — not as a category of subjective expression, but a cultural trope that is complicated by the disjunction and the interrelation between the self and the world, the contingent and the transcendent [3]. Details about the song, both musical and historical, together perfectly encapsulate the spirit of Hoang Duong Cam’s seventh solo show with Galerie Quynh as the artist continues his tireless personal interrogation and rumination on distance and liminal space, as well as the slippery boundary between absurdity and fact.

Through extensive artistic research, which is grounded in his understanding and interpretation of fine arts traditions, music, history, and literature, Hoang Duong Cam has long been interested in identifying gaps as parameters for distance and intimacy in existing structures or compositions. In the seminal Rest Energy (1980), the acclaimed performance duo Marina Abramovic and ULAY held a bow with their body weight with the arrow directed towards Abramovic’s heart; two small microphones were placed on their hearts. The tension between the two, who were partners in art and in life, was intensified by the sound of their amplified heartbeats. Later, Abramovic described the experience, though lasting only four minutes and ten seconds, feeling like forever [4] as she had no control over the situation, thus relying entirely on her trust in ULAY. Hoang Duong Cam has always been intrigued by how the duo examined spatial and mental distance in human relationships in their works, which to him managed to disrupt and redefine the distinction between near and far. Cam is also drawn to how musical geniuses see the gap, however small, in classical music — a genre notorious for its strict predetermined compositions. Midori Gotō is a Japanese-born American violinist — a child prodigy and celebrated musician to the world, but to Hoang Duong Cam she is someone who could deconstruct and reconfigure classical music through her body movements. When Midori performs Chaconne by Bach, her entire body moves in tandem with the twists and turns of the melody, thus letting her individuality infiltrate a seemingly unwavering structure.

Another area of interest to Cam is how historical landmarks have played the role of reluctant witnesses of major upheavals that caused mass migration. Decades after the Vietnam War, the once brutal, deathly battlefields such as Dong Thap Muoi, Hue, Quang Tri, Xuan Loc are now sites of peacetime and modernity. Receding to the background of these landscapes, what is left of that painful era now only exists in the form of archival war photographs, documentaries, and Hollywood productions, which for a while have been the main forms of evidence to understand the socio-political conflicts of that period. In his attempts to make sense of his own reality, Cam reimagines history by juxtaposing different timelines, sceneries, and figures against one another — a tedious experiment that helps ease his own cynicism for the linearity of official history. Another prominent inspiration in this series of paintings is Sunlight in the Garden (1938), a short story written by Vietnamese author Thach Lam, which revolves around a young love that eventually ends in separation and regret. The way Thach Lam likens the couple’s naivety and their inevitable parting to how pure and natural sunlight drapes the garden in its beautiful glory prompts Hoang Duong Cam to adopt a palette of well-measured colours. While not as dramatic and vivid as in his previous works, the colours he uses now have mellowed out, yet still retain a vibrancy.

LACHRIMAE embraces the identity of an intricate labyrinth that materialises as the artist weaves together his observations, compositional reappropriations, and his own hypotheses. It is a common practice to dissect an abstract painting by identifying the values of negative and positive spaces, which leads to the understanding of forms and composition. Positive space is thought to carry the creative actions and aesthetic manifestation of a painting, while its counterpart is considered as the less important background [5]. Cam’s works prove otherwise as it is impossible to identify the positive from the negative. Each layer, whether having forms or free brushstrokes, represents a detail or a line of thought that is indispensable to the making of the whole painting. Packed with speculative references and anecdotes, these paintings invite viewers to keep shifting their perspectives in order to see the distance and proximity, which have haunted the artist for so long.

of the Fold.”[4] “Marina Abramović and ULAY. Rest Energy. 1980.”[5] Kočíb, “Quasi-Negative Space in Painting.”

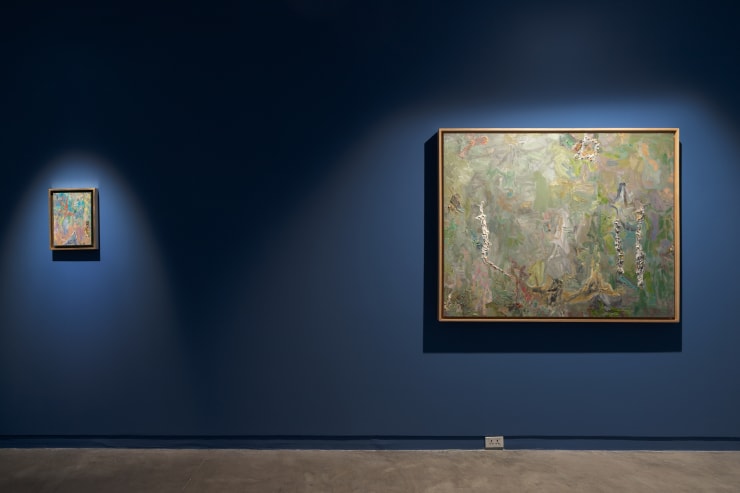

Installation Views

Works

-

Hoang Duong Cam, After Hiroshige’s fireworks and Linebacker 2, 2011-2021

Hoang Duong Cam, After Hiroshige’s fireworks and Linebacker 2, 2011-2021 -

Hoang Duong Cam, Concerto for Oboe in D minor, Adagio by A. Marcello, 2021

Hoang Duong Cam, Concerto for Oboe in D minor, Adagio by A. Marcello, 2021 -

Hoang Duong Cam, Sunlight in the Garden - Xuan Loc, 2020

Hoang Duong Cam, Sunlight in the Garden - Xuan Loc, 2020 -

Hoang Duong Cam, Pre-helicopter Era, Michael Rabin in the middle of Dong Thap Muoi or Bach Violin Sonata 1005 Adagio, 2021

Hoang Duong Cam, Pre-helicopter Era, Michael Rabin in the middle of Dong Thap Muoi or Bach Violin Sonata 1005 Adagio, 2021 -

Hoang Duong Cam, Post-helicopter Era, Michael Rabin in the middle of Dong Thap Muoi or Bach Violin Sonata 1005 Largo, 2021

Hoang Duong Cam, Post-helicopter Era, Michael Rabin in the middle of Dong Thap Muoi or Bach Violin Sonata 1005 Largo, 2021 -

Hoang Duong Cam, Sunlight in the Garden - Hue, 2021

Hoang Duong Cam, Sunlight in the Garden - Hue, 2021 -

Hoang Duong Cam, Sunlight in the Garden - Quang Tri, 2021

Hoang Duong Cam, Sunlight in the Garden - Quang Tri, 2021 -

Hoang Duong Cam, Prokofiev Violin Concerto No. 1 - Ha Tuyen, 2021

Hoang Duong Cam, Prokofiev Violin Concerto No. 1 - Ha Tuyen, 2021 -

Hoang Duong Cam, Chopin Sonata No. 1 - Mr. Horst Fass’ drifted lens tank, 2021

Hoang Duong Cam, Chopin Sonata No. 1 - Mr. Horst Fass’ drifted lens tank, 2021 -

Hoang Duong Cam, Lachrimae, 2021

Hoang Duong Cam, Lachrimae, 2021 -

Hoang Duong Cam, Kubrick’s Hue Scene or Midori Goto playing Bach’s Chaconne 1004, 2021

Hoang Duong Cam, Kubrick’s Hue Scene or Midori Goto playing Bach’s Chaconne 1004, 2021 -

Hoang Duong Cam, Bach 826 Courante, 2021

Hoang Duong Cam, Bach 826 Courante, 2021 -

Hoang Duong Cam, Sunlight in the Garden - Troi giat, 2021

Hoang Duong Cam, Sunlight in the Garden - Troi giat, 2021 -

Hoang Duong Cam, Prokofiev Violin Concerto No. 2 – Quang Tri, 2021

Hoang Duong Cam, Prokofiev Violin Concerto No. 2 – Quang Tri, 2021 -

Hoang Duong Cam, Sunlight in the Garden - Quang Ba, 2020

Hoang Duong Cam, Sunlight in the Garden - Quang Ba, 2020 -

Hoang Duong Cam, On Soil On Water, 2018

Hoang Duong Cam, On Soil On Water, 2018